At Nordic Schools we work with school improvement in several countries. Therefore, we have teamed up with educational consultant, Dr Jim Rogers because we want the Scandinavian school systems to inspire the Continuing Professional Learning in British and international schools.

Below you can read Jim’s excellent blog about what UK school leaders and teachers can learn from the Scandinavian schools in Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland.

Enjoy!

HOW IT ALL BEGAN…

I first met Casper and colleagues at a conference for headteachers in Dorset, England in 2016. I won’t go into any murky details, but we were all presenting at the conference. I remember being introduced and, having just been to Norway, blurted out how much I loved Norway and its people. Casper smiled politely and waited until I had finished before saying “that’s nice. We are from Denmark”. The rest of the conference was a blur of headteachers and alcohol. Welcome to the English education system, Casper! We have kept in touch since, I have visited Denmark several times and I am delighted to now be collaborating through a more formal partnership.

So, I have been to Norway, visited schools in Sweden and now in Denmark. I have yet not been to the elusive Finland. The Scandinavian countries have an international reputation for the quality of their education systems; schools generally perform well in international educational measures (as do we here in England such as TIMSS, PISA, PIRLS), but the countries are also known for their ‘happiness’, quality of life, hygge and egalitarianism (and Law of Jante!).

THE QUESTION IS…

What can these countries inform us about our education systems?

This is a question I have pondered for several years now, and the more I learn, visit and reflect, the more I think we can benefit from some of the things the Scandinavian countries get right.

The pandemic has highlighted some quite staggering practice from our educational professionals. While we have always had to deliver education against changing politics and policies, the last twelve months has demonstrated just how effective schools have been in doing this. But there are a couple of things our Nordic colleagues do well, embedded in their culture and practice, and they are things that we are beginning to realise are really important. That is wellbeing, relationships and rapport. I am going to take relationships and rapport as the focus of this blog and tell you what I have seen and how I apply this to professional learning programmes I lead in England.

THE ENGLISH CONTEXT FIRST

Let’s briefly explore the English context. If you look at the Teaching Standards, ‘minimum standards for teachers’ practice and conduct’ that all teachers need to ‘evidence’ in their probationary first year, there is some, but very little reference to relationships:

‘maintain good relationships with pupils, exercise appropriate authority, and act decisively when necessary’ in relation to ‘7. Manage behaviour effectively to ensure a good and safe learning environment’. (DfE, 2011)

The rhetoric is about behaviour, not the importance of relationships and rapport in order to support students to be ready and receptive to learning. There are no references to relationships and rapport in standards 4 or 5 (look them up!).

There has been a recent push from government ministers and the Department for Education (DfE) on ‘behaviour and discipline’. In the ‘Behaviour and Discipline in Schools Advice for Headteachers and School Staff’ (DfE, 2016) the one reference to relationships is regarding fostering good relationships with home / school. In the ‘Checklist for School Leaders to Support Full Opening: Behaviour and Attendance’ (DfE 2020) there is no reference to relationships whatsoever. Yet the research, and our experience, tells us how important this is.

SO, WHAT DOES THE RESEARCH SAY? THE TRANSFORMATIVE POWERS OF FEELING SAFE

In December 2019 the Education Endowment Foundation published an evidence review on Improving Behaviour in Schools. In this report six recommendations are made, and the relevant ones are:

- Understanding a pupil’s context will inform effective responses to misbehaviour.

- Every pupil should have a supportive relationship with a member of school staff.

- Teachers can provide the conditions for learning behaviours to develop by ensuring pupils can access the curriculum, engage with lesson content and participate in their learning.

What is significant about the review is that while it frames the focus on ‘improving behaviour’ it acknowledges learning behaviours, the role of the teacher in fostering these, understanding the learners’ context and having a ‘supportive relationship’ with pupils. It is not about discipline or compliance, it is about a duty of care, an understanding of the emotional needs of a student, and creating the right conditions for trust and safety required for learning to take place.

I worked with Ian Hunkin of Sigma Teaching Alliance last year and learnt a lot about the ‘transformative powers of feeling safe’. He cited Porges’ Polyvagal Theory and Dr Bruce Perry’s work on the impact of trauma on children. We have a tremendous duty of care at the moment for the wellbeing of our children particular as they return to school, and in order to have the best chances of success we need to work hard to ensure children feel safe regardless of social distancing, face masks or zoning of schools. The quality of our relationships and development of rapport with the children is therefore critical. Never has this been so important.

ITS ALL ABOUT…TRUST

It is the social and emotional teaching competencies that appear embedded within the Nordic approach to teaching. If I had to summarise the education system and schools that have visited in one word it would be ‘trust’. Trust is seen at one scale from teacher to pupil and vice versa all the way through the system to local authorities and national policy. And while there will be multiple individual and cultural factors that contribute towards this, I believe the quality of the relationship between staff and teachers and pupils is central to the success.

BUT WHAT ABOUT ‘ZERO TOLERANCE’?!

My hunch is this: we are social beings. We appear to socially construct knowledge and we are far more effective when we work collectively than when we work in isolation. We are the only species of primate that can work with strangers at scale around fictitious constructs such as education for example (Harari, 2014). So, while schools are complex social environments, at their very heart is the relationships and report between professionals and between professionals and students. Without quality relationships we are adopting a mechanistic, industrial model of education (see Ken Robinson’s RSA Animate)

In addition, in my view, any effort to improve the quality of teaching and learning and to take into account pedagogical principles needs to be delivered on a strong foundation of effective relationships and rapport. It should not be based on ‘zero tolerance’ which leads to compliance and disengagement, but about quality relationships, learning behaviours, based on good rapport.

Behaviour management is often a big challenge for recently qualified teachers. And without the emphasis and investment in supporting these teachers and developing high quality relationships and rapport we are at risk of further retention challenges.

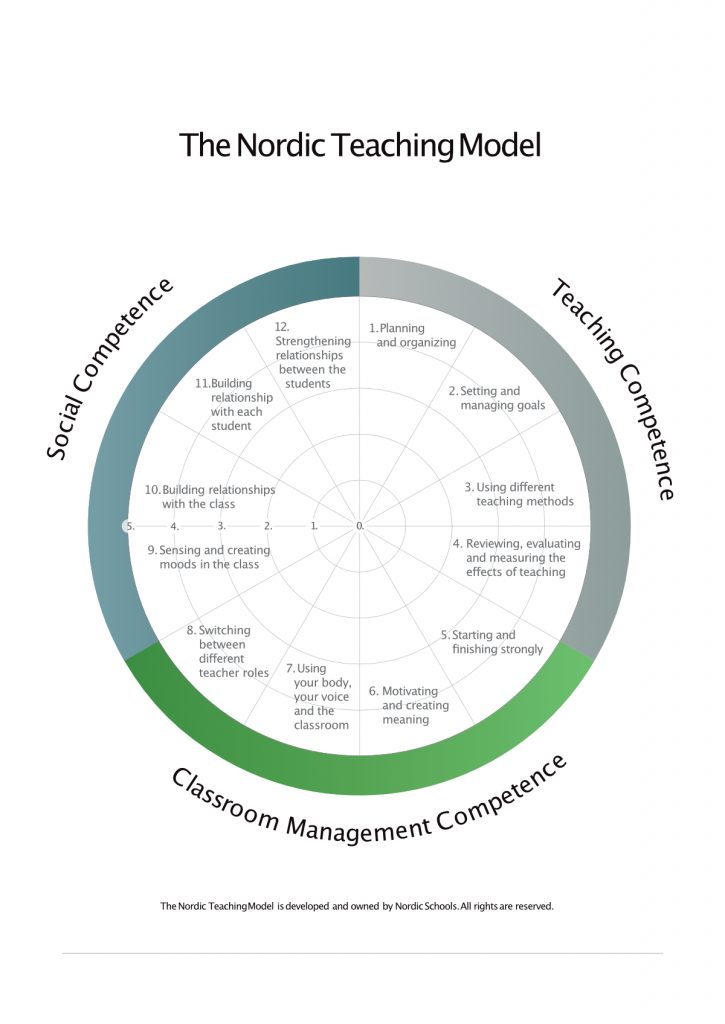

I wonder if part of the problem is that relationships and rapport are very personal, hard to define, and often perceived as entirely down to personality and intuition? This is where the work that my colleagues in the educational consultancy Nordic Schools is so important. They have recognised that one of the key strengths of the Scandinavian school systems is that high quality relationships and rapport as an explicit teaching competence and have defined this within their Nordic Teaching Model.

CAN WE ACTUALLY DEVELOP RELATIONSHIPS AND RAPPORT?

What the gentlemen from Nordic Schools have done here is carefully define what they consider to be the competencies required to be an effective teacher. What I like about this is the focus on the ‘softer skills’ such as social competencies. If you were to compare the model with the Teaching Standards you will see very little overlap and a very different rhetoric. The model is also a reflective tool. Using the wheel, teachers reflect on their strengths and weaknesses and prioritise actions.

I use the model at the start of many of the professional learning programmes I deliver. It is useful to begin with reflection and focus on the more subtle skills required to be an effective teacher. Of all the competencies ‘11’ is the one most ‘novice’ teachers highlight as a priority. Less experience, less time in a school or with a class, pressures of transitioning from training to a full-time teaching job may all be factors.

When I work with teachers the focus is often about quality teaching and exploring learning theory and pedagogy. I take the approach that changes in professional behaviours are more achievable and sustainable if the teachers take ownership of their own learning. Therefore, a component of the programmes is often to lead an enquiry into their own practice, exploring research evidence and developing strategies to trial and test in the classroom.

PUTTING IT IN TO PRACTICE

Three years ago, I was asked to provide a keynote for a group called Babcock International at the army base in Lyneham, Wiltshire. The audience: The Defence School of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering, MOD and Babcock training staff. An audience of hardened military or ex-military professionals, the majority in uniform. Rarely do I get nervous but standing in front of this audience to talk about ‘relationships and rapport’ was certainly a challenge. What I found interesting was that they had selected this topic, recognising it was key to successful delivery and learning on their huge base where soldiers from every regiment visited at some point to learn about how to use, service and fix technical equipment ‘in the field’. Anecdotally I understand that many of the training staff adapted their approach following the conference, investing time in to developing rapport and knowing their learners’ needs to inform planning.

The RQTs and Social Competence

I am working with a group of recently qualified teachers for the Castle Partnership Trust in Somerset, England. The teachers are about to embark on their own professional career journey. I know several of the teachers at the beginning of the programme shared they were struggling with relationships and rapport of some groups, impacting on their teaching and other students’ learning. This will become the focus of their enquiry. What is particularly exciting and timely is the Nordic Schools have created a new free online course:

Social Competence and Relationship Overview’. It consists of short videos, podcasts and articles and is very inspiring for British school leaders and teachers. And thought provoking!

This course will form the beginning of the enquiry and help shape reflection, strategy and action. Later this year I will write-up the enquiry as another blog – to provide you with some case-studies and model practice.

Dr Jim Rogers

Dr Jim Rogers is an education specialist working nationally and internationally with schools and training organisations. He specialises in evidence-informed professional learning and is the regional CPD and Research Lead for the Teaching School Council SW, a Founding Fellow for the Chartered College, a partner of the Nordic Schools and an ambassador for the Global Education Collective. www.jimrogerstraining.co.uk

REFERENCES

DfE (2016) ‘Behaviour and Discipline in Schools Advice for Headteachers and School Staff’

DfE (2020) ‘Checklist for School Leaders to Support Full Opening: Behaviour and Attendance’

EEF Guidance Report (2019) Improving Behaviour in Schools: An Evidence Review.

Harari (2014 ) Sapiens A brief history of humankind

Meredith (2020) Behaviour is about relationships. The DfE ignores this.

RSA Animate: Changing Education Paradigms. Sir Ken Robinson.

We hope that you have enjoyed Jim’s blogpost about what British schools can learn from the Scandinavian schools.

Are you interested in learning more about what we do at Nordic Schools? Sign up for our newsletter below.

If you are not the newsletter type that is fine too. Maybe you are more of a social media type? You can follow us on these platforms: